When you’re hunting for ancient jewels in ruins, you’ll discover artifacts that span from 170,000-year-old perforated shell beads in Morocco’s Bizmoune Cave to Bulgaria’s Varna Necropolis gold pieces dating to 4600 BC. Archaeological excavations reveal sophisticated metalworking techniques like Sumerian granulation and filigree, composite necklaces combining Afghan lapis lazuli with Iranian carnelian, and ritual deposits containing thousands of precious items. These findings document early trade networks, social hierarchies, and symbolic communication systems. The evidence preserved in burial sites and ceremonial contexts illuminates humanity’s technological innovations and cultural expressions throughout prehistoric societies.

Key Takeaways

- Varna Necropolis in Bulgaria yielded over 3,000 gold objects from 4600–4200 BC, with 30% remaining unexcavated for future discoveries.

- Ancient burial sites like Queen Pu-Abi’s tomb and Grave 43 contain sophisticated jewelry, revealing metalworking techniques and extensive trade networks.

- Bizmoune Cave in Morocco produced 33 shell beads dated 142,000–171,000 years ago, the earliest known human adornment evidence.

- Troy served as a Bronze Age metallurgical hub where relocated Mesopotamian workshops created gold artifacts using advanced granulation and filigree.

- Viking Age sites like the Hiddensee Treasure and Pictish forts contain elite jewelry demonstrating cultural exchange and social hierarchy symbolism.

The Earliest Adornments: Shell Beads From Prehistoric Morocco

Between 2014 and 2018, an international team excavated Bizmoune Cave in western Morocco, located 12 kilometers east of the Atlantic Ocean, and recovered 33 perforated shells that represent the earliest known personal adornments in the archaeological record.

These thumbnail-sized Tritia gibbosula specimens, found within ashy silt alongside stone tools and animal bones, date between 142,000 and 171,000 years old based on uranium decay analysis. You’ll find central perforations—rare in naturally occurring shells—that enabled stringing as beads.

Red ochre staining appears on several specimens. This prehistoric ornamentation extends bead-making evidence 10,000 to 20,000 years earlier than previous records, demonstrating marine shell symbolism’s role in expressing identity and expanding social networks.

The discovery confirms North Africa’s contribution to nonverbal communication origins through deliberate body decoration practices. Similar evidence of ancient human activity has been found across the Middle East, Israel, Algeria, and South Africa. Researchers suggest these beads may have signaled clan membership or partnership status, facilitating interactions within social groups or between strangers.

Varna’s Golden Treasures: The Oldest Worked Gold in History

You’ll find the world’s oldest worked gold at the Varna Necropolis in Bulgaria.

Excavations between 1972 and 1991 revealed 3,000 gold artifacts weighing six kilograms and dating to 4600–4200 BC. The site’s accidental discovery by excavator operator Raycho Marinov led to systematic archaeological investigation that uncovered 294 graves.

Seventy of these graves contained gold objects ranging from miniature cylinders measuring 2×2 mm to elaborate breastplates and scepters. The artifacts demonstrate sophisticated metallurgical techniques that predate comparable finds from Mesopotamia and Egypt by centuries. Grave 43 contained the most gold of any burial at the time of discovery, initially believed to belong to a prince but later identified as a smith’s grave. Evidence suggests trade with distant lands, including the lower Volga and Cyclades, through artifacts like Mediterranean Spondylus shells.

This establishes Varna as the earliest evidence of complex goldworking in human history.

Discovery at Varna Necropolis

While preparing ground for a canning factory near Varna, Bulgaria, excavator operator Raycho Marinov made an unexpected discovery in October 1972 that would fundamentally alter archaeological understanding of prehistoric metallurgy and social organization.

Dimitar Zlatarski of Dalgopol Historical Museum recognized the site’s significance, prompting government intervention. Excavations from 1972–1991, led by Mihail Lazarov and Ivan Ivanov, revealed the Varna Chalcolithic Necropolis.

Radiocarbon dating in 2006 confirmed 294 graves spanning 4,569–4,340 BC, with ancient mining activities evidenced by gold artifacts dating to 4,600–4,200 BC. Approximately 30% of the necropolis remains unexcavated, indicating substantial archaeological potential yet to be explored.

You’ll find over 3,000 gold objects weighing 6.5 kilograms—the world’s oldest worked gold. These artifacts include necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and beaded pendants showcasing the earliest known gold craftsmanship. These ritual burials, particularly symbolic graves containing clay masks and gold exceeding 5 kilograms combined, demonstrate unprecedented craftsmanship predating Mesopotamian and Egyptian gold by millennia.

Gold Artifacts and Techniques

The Varna Necropolis holds over 3,000 gold artifacts weighing more than 6 kilograms collectively, dating from 4600 BC to 4200 BC—establishing them as the world’s oldest processed gold. You’ll find this collection exceeds all combined gold artifacts from other 5th millennium BC sites globally, predating Sumerian and Egyptian finds by over 1000 years.

Ancient goldsmithing techniques demonstrate remarkable sophistication. Craftsmen hammered, shaped, and decorated gold with exceptional purity. The artifacts—pendants, bangles, scepters, diadems, and ceremonial axes—reveal organized metallurgical evolution by 4600 BC. Gold was sourced from Sredna Gora mountains, where advanced processing techniques were developed to extract and refine the precious metal.

High-temperature kilns originally developed for pottery enabled advanced copper and gold processing. The gold exhibits extraordinary purity levels of 23.5k-24k, surpassing the metallurgical capabilities typically attributed to ancient civilizations of that era.

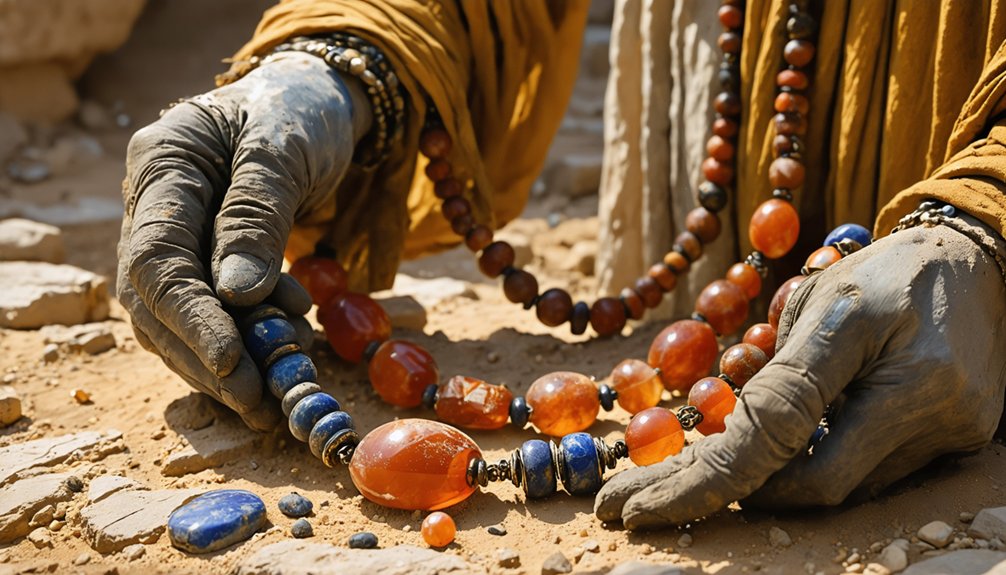

Three elite graves contain ceremonial scepters symbolizing supreme authority, while gold-sheathed axes and intricate jewelry display unprecedented technical mastery. One carnelian bead even conceals a 2x2mm gold mini-cylinder, showcasing microscopic precision.

Sumerian Mastery: Filigree and Granulation Techniques

You’ll find the earliest evidence of granulation technique in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, where Queen Pu-Abi’s tomb yielded examples dating to 2500-2750 BCE.

The Sumerians developed this method of fusing tiny gold spheres onto metal surfaces without hard solder, alongside filigree work that welded twisted metal threads onto sheet backgrounds. These early examples showed primitive work, indicating initial experimentation with the process. The Sumerians likely imported metals while demonstrating exceptional skill in working with gold and silver.

Following Ur’s destruction, these techniques spread westward through Asia Minor to Troy and the Mediterranean regions, establishing what scholars term the “Ex Oriente Lux” transmission path from Mesopotamia.

Origins in Ancient Mesopotamia

Deep within the ancient ruins of Mesopotamia, archaeologists discovered relics of filigree design dating to 3000 BC, marking humanity’s earliest known experiments with sophisticated metalworking techniques.

You’ll find evidence of ancient metallurgy throughout Sumerian sites, where craftsmen pioneered early adornment techniques that revolutionized personal decoration.

The Sumerians introduced these innovations around 2750 BCE:

- Granulation gold jewelry excavated from Queen Pu-Abi’s tomb in Ur between 1922 and 1934

- Primitive granulation techniques estimated at 5000 years old

- Origins traced specifically to 2500 BCE in Mesopotamian culture

- Advanced skills combining religious significance with artistic expression

These craftsmen didn’t simply create jewelry—they invented it.

Their mastery of twisting gold and silver wires, coupled with colloidal soldering methods, established foundations you’ll recognize in contemporary metalworking practices worldwide.

Spread to Troy Region

Between 2500 and 2300 BC, Sumerian metalworking techniques migrated westward across trade routes to Troy in present-day Turkey. Archaeologists uncovered gold jewelry bearing unmistakable hallmarks of Mesopotamian craftsmanship.

You’ll find filigree and granulation methods—twisted wires and soldered spheres—identical to pieces from Queen Pu-Abi’s tomb at Ur. Laser ablation analysis confirmed that Troy’s gold shared platinum and palladium ratios with Mesopotamian sources, proving direct material connections.

Trade networks carried not just precious metals but specialized knowledge, evidenced by standardized spiral earrings and stone-inlaid rings using lapis lazuli and carnelian. Heinrich Schliemann’s Priam’s Treasure, though misattributed, contained 61 artifacts demonstrating these craftsmanship techniques.

After Ur’s destruction around 2000 BC, workshops relocated westward, establishing Troy as a vital node in Bronze Age metallurgical innovation.

Bronze Age Discoveries: From English Barrows to Levantine Sites

Across Bronze Age Europe and the Near East, archaeological excavations reveal distinctive patterns in jewelry deposition that illuminate ancient social hierarchies and belief systems. You’ll find ancient craftsmanship manifested differently across regions—from Leicestershire’s composite necklaces (1750-1500 BC) crafted from non-local materials to Varna’s nobleman tomb (4569-4350 BC) containing gold bracelets and weaponry.

The ritual symbolism varies considerably: English barrows show extended wear patterns indicating heirloom status, while Bulgarian burial mounds suggest communal ritual property distinct from elite collections.

Key regional patterns include:

- British Isles: 1,500 surviving gold objects, including Irish lunulae and gorgets

- Levantine sites: Identical carnelian pod pendants across Deir el-Balah, Mari, and Assur

- Switzerland: Bronze discs with amber beads and protective amulets (1500 BC)

- Failaka: Semiprecious stones from India/Pakistan indicating Dilmun trade revival

Decoding Ancient Trade Routes Through Composite Jewelry

The materials composing Bronze Age jewelry reveal complex international exchange systems that connected distant civilizations centuries before formal trade agreements. You’ll find composite necklaces from Early Dynastic Mesopotamia combining Afghan lapis lazuli, Iranian carnelian, and Anatolian gold—each component documenting a specific supply chain.

Ancient metallurgy techniques themselves traveled these routes: Sumerian granulation methods reached Troy by 2500 BC, while Chinese filigree merged with Persian traditions along Silk Road corridors.

Trade route symbolism appears in recurring motifs like the Tree of Life, found across Middle Eastern and Central Asian artifacts. Archaeological evidence at Persepolis and Tepe Sialk confirms Iran’s position as a synthesis center where Indian emeralds met Nishapur turquoise in finished pieces destined for Roman markets.

Norse and Pictish Legacies: Baltic and Scottish Finds

You’ll find the Hiddensee Treasure’s gold collection exemplifies Norse craftsmanship along Baltic trade networks, dated to the 10th century through comparative analysis with Scandinavian ornamental traditions.

The Pictish garnet ring discovery in north-east Scotland demonstrates material exchange between Mediterranean sources and Pictish territories, documented through geological sourcing studies of the garnets’ volcanic origins.

Celtic gold collar techniques, preserved in both Baltic and Scottish archaeological contexts, reveal shared metalworking knowledge transmitted via northern European maritime routes between 300 BCE and 700 CE.

Hiddensee Treasure Gold Collection

Between 1872 and 1874, storm tides eroded the northern coastline of Hiddensee, a German Baltic island. This process revealed sixteen gold artifacts that comprise one of medieval Europe’s most significant Viking Age treasures.

You’ll find this collection represents exceptional ancient craftsmanship from around 1000 CE, with all pieces sharing nearly identical chemical composition indicating gold purity of remarkable consistency.

The hoard’s significance centers on several distinguishing features:

- Royal Provenance: Likely belonged to Danish King Harald Bluetooth’s family

- Technical Excellence: Crafted by experienced goldsmiths using sophisticated methods

- Power Display: Cross-shaped pendants measuring nearly 7 cm demonstrated elite status

- Rarity: Extraordinary compared to 100+ smaller Hiddensee-style items, mostly silver

You can examine these artifacts at Kulturhistorisches Museum Stralsund, where they’ve remained since discovery. This setting offers unmediated access to Viking political and religious transformation.

Pictish Garnet Ring Discovery

While Viking treasures illuminate medieval Scandinavia’s reach across the Baltic, archaeological discoveries in northeastern Scotland reveal the contemporaneous Pictish civilization that dominated the region from the 3rd through 9th centuries AD.

You’ll find concrete evidence at Burghead Fort in Moray, where volunteer John Ralph unearthed a kite-shaped Pictish ring during the final day of excavation. The near-complete garnet-centered piece survived over 1,000 years underground—remarkable considering 1800s construction previously obscured the site.

Professor Gordon Noble identifies it as one of few Pictish rings discovered outside hoards, providing direct insights into power structures. The fort served as a significant Pictish center from 500-1000 CE, with ancient pottery, ritualistic symbols, and metalworking evidence confirming its importance before Gaelic absorption ended their recorded history.

Celtic Gold Collar Techniques

Across Iron Age Europe, Celtic goldsmiths developed sophisticated torc fabrication methods that required mastering both metallurgical science and artistic precision. Ancient goldsmithing demanded you understand complex joining techniques, from mortice-and-tenon fastening systems to temperature-controlled soldering that prevented metal from melting.

Celtic metallurgy evolved dramatically across regions and periods:

- Broighter Hoard (1st century BC): Single gold sheet formed into torcs with precise La Tène bird and horse motifs.

- Pulborough fragments (4th-3rd century BCE): Hollow construction with 61-63% gold, 35-37% silver alloy.

- Borrisnoe Collar (750 BC): Intricate forms from soft gold featuring wire loops for attachment.

- Mooghaun Horde: Over 150 hammered ornaments representing centuries of craft evolution.

You’ll find these techniques reveal how artisans concealed complex fabrication beneath deceptively simple designs.

Egyptian Innovation: Faience and Glass Bead Substitutes

This innovation preceded glass by over 1,500 years, offering you insight into early material experimentation. Artisans shaped faience into scarabs, cylinders, and discs—each carrying cultural symbolism tied to fertility and eternal life.

Archaeological evidence from Naqada and Badari reveals these beads adorned both living and dead, with intricate mummy bead patterns demonstrating sophisticated weaving techniques.

Precious Stones of the Ancient World: From Peridot to Cat’s Eye

Beyond the crafted substitutes of faience and glass, ancient civilizations pursued gemstones that occurred naturally in Earth’s crust, each valued for distinct optical properties and cultural significance.

Natural gemstones transcended mere decoration, embedding geological rarity into the fabric of ancient power structures and cross-continental commerce.

You’ll discover these stones carried specific attributions:

- Peridot – Cleopatra’s palace showcased these Red Sea gems around 330 BC, establishing royal status markers.

- Cat’s Eye – Chinese warriors incorporated chrysoberyl into armor circa 200 BC for protective qualities.

- Lapis Lazuli – Sumerians combined Afghan imports with gold from 2500 BC for deity associations.

- Carnelian – Mediterranean craftsmen created signet rings over 4500 years ago.

Modern gemstone synthesis and ethical sourcing debates reflect contemporary values, yet these ancient extraction practices reveal how societies prioritized access to rare materials. You’re examining evidence of trade networks spanning continents, where gemstone acquisition determined social hierarchies.

Rare Materials and Early Metalworking: Platinum and Diamonds

While ancient civilizations readily identified and worked colored gemstones through conventional heating and shaping methods, platinum presented metallurgical challenges that defied standard techniques until cultures developed innovative workarounds.

Ancient platinum first appeared accidentally in Egyptian gold artifacts around 700 BCE, arriving as unwanted contamination from Nubian ores. The dense metal’s chemical inertness prevented separation during purification, frustrating artisans who viewed it as inferior material.

Pre Columbian metallurgy achieved what Egyptians couldn’t—intentional platinum craftsmanship. Ecuador’s La Tolita culture (600 BCE-200 CE) pioneered powder metallurgy, grinding platinum and fusing it with gold, silver, and copper.

Archaeological evidence from Las Balsas dates platinum use to 915-780 BCE. These metalworkers created sophisticated nose rings and ceremonial objects through deliberate alloying, demonstrating mastery over materials that wouldn’t yield to European techniques until centuries later.

Symbolic Meanings: Jewelry as Offerings and Status Markers

Archaeological evidence reveals that ancient jewelry functioned as far more than decorative ornament—these objects encoded complex social hierarchies, regulated community relationships, and served as intermediaries between the living and spiritual domains.

Ancient jewelry transcended mere adornment, encoding social hierarchies and bridging mortal communities with spiritual realms through ritualized material culture.

You’ll find compelling evidence across multiple civilizations:

- Bronze Age Polish communities deposited 550+ jewelry pieces in wetlands as ritual offerings, marking a deliberate shift from human remains to metal objects.

- Roman elite burials contained gold necklaces, silver rings with amber, and engraved initials—skeletal analysis confirmed no physical labor stress.

- Sardis necropolis graves featured cloth appliqués depicting royal sphinxes, signifying rank through symbolic imagery.

- Proximity to exclusive Roman establishments correlated directly with burial richness and precious stone quantities.

These patterns demonstrate how jewelry ritual practices simultaneously reinforced social hierarchy while connecting communities to supernatural protection.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Archaeologists Determine the Authenticity of Ancient Jewelry Finds?

You’ll verify authenticity through microscopic examination of manufacturing techniques, XRF testing of metal composition, and artifact reconstruction from excavation contexts. Cultural significance emerges when provenance documentation links pieces to verified archaeological sites with controlled excavation records.

What Preservation Methods Prevent Ancient Jewelry From Deteriorating After Excavation?

You’ll rescue fragile treasures through chemical treatments that neutralize corrosive chlorides, then seal artifacts in controlled environments with oxygen scavengers and moisture barriers. Custom supports prevent structural collapse while anoxic microclimates guarantee your discoveries survive for future generations to study.

Can Metal Detectors Locate Jewelry Buried Deep in Archaeological Ruins?

Metal detection locates jewelry in archaeological exploration, but you’re limited to shallow depths of 8-12 inches. For deeper ruins, you’ll need traditional excavation methods, as standard detectors can’t penetrate beyond the plow zone effectively.

How Are Ancient Jewelry Discoveries Valued for Museums or Collectors?

You’ll find ancient jewelry valued through meticulous appraisal combining historical context and cultural significance with provenance documentation. Museums prioritize authenticity, excavation records, material quality, craftsmanship techniques, and rarity—factors determining whether pieces command thousands or exceed six figures at auction.

What Legal Protections Exist for Ancient Jewelry Found on Private Property?

Legal regulations typically override your ownership rights when you discover ancient jewelry on private property. National vesting laws often declare archaeological finds state property, requiring immediate notification to authorities regardless of where you found them.

References

- https://www.futura-sciences.com/en/a-grave-shakes-history-the-first-gold-jewelry-of-humanity-was-here_25062/

- https://news.artnet.com/art-world/worlds-oldest-jewelry-morocco-2037635

- https://www.langantiques.com/university/ancient-jewelry/

- https://norsespirit.com/blogs/norse_viking_blog/3-fascinating-archaeological-discoveries-of-ancient-norse-jewelry

- https://www.gemsociety.org/article/myth-magic-and-the-sorcerers-stone/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43kbJlDSK5A

- https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/archaeology/a70259313/archaeologist-finds-ancient-pictish-ring-implications/

- https://ajaonline.org/online-museum-review/368/

- https://robinsonsjewelers.com/blogs/news/archeological-discoveries-that-changed-our-understanding-of-ancient-jewelry-the-bling-of-our-ancestors-revealed

- https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-history-of-jewellery