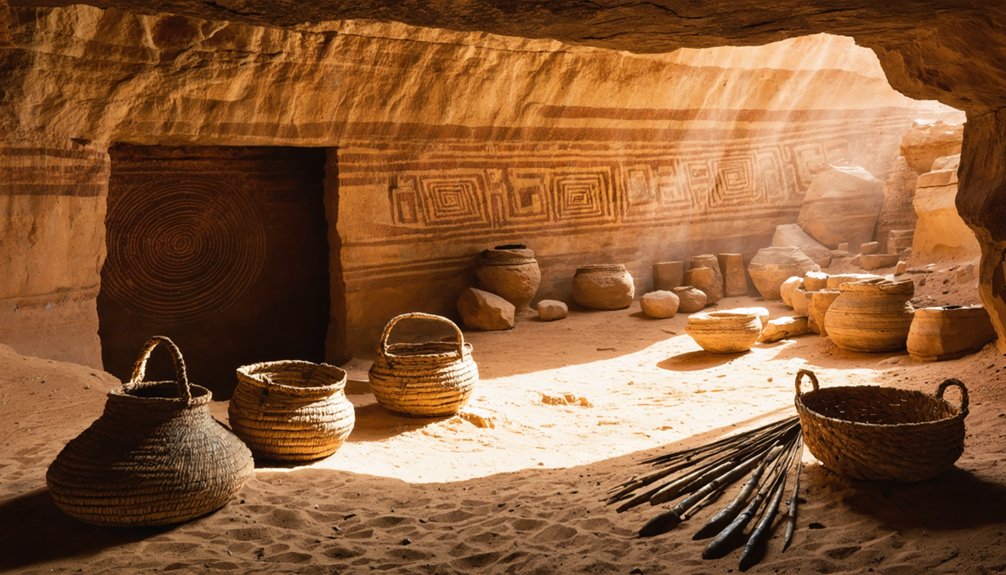

You’ll find Ancestral Puebloan artifacts primarily in Four Corners archaeological sites, accredited museums housing 150,000+ catalogued specimens, and protected rock art locations. Edge of the Cedars State Park contains the region’s largest pottery assemblage, while Arizona State Museum preserves extensive collections. Since ARPA’s 1979 enactment, surface collection on federal lands is prohibited—artifacts remain in situ or within institutional repositories. These ceramics, including Tularosa Black-on-White and Four Mile Polychrome pieces, reveal sophisticated mineral pigment techniques and trade networks that extended from Pacific Coast to Rio Grande pueblos, with thorough documentation throughout the following analysis.

Key Takeaways

- Edge of the Cedars State Park houses the largest pottery assemblage in the Four Corners region with extensive artifact collections.

- Arizona State Museum and Museum of Indian Arts and Culture maintain significant holdings of over 150,000 Ancestral Puebloan artifacts.

- Anasazi State Park Museum provides access to excavated materials from Coombs Site, showcasing household and ceremonial pottery.

- Artifacts include Black-on-White pottery, corrugated cooking vessels, polychrome jars, turquoise pieces, obsidian, and Pacific shells from trade networks.

- NAGPRA compliance since 1990 governs artifact preservation, affecting how museums collect and display Ancestral Puebloan materials.

Primary Pottery Styles and Their Distinctive Features

Black-on-White pottery represents the most widespread Anasazi ceramic tradition, characterized by mineral-based paints that fire to black against white-slipped clay bodies.

You’ll identify intricate geometric patterns—zigzags, triangles, interlocking barbed lines—displaying reflective and rotational symmetry. Tularosa Black-on-White exemplifies peak craftsmanship from 1150-1325 AD.

Tusayan White Ware parallels Red Mesa styles but features bolder patterns with interlocking hooked scrolls and negative painting techniques.

Kayenta variants display distinctive banded designs.

Corrugated Ware serves utilitarian functions—its unsmoothed coiled construction resists thermal shock during cooking and improves boiling efficiency.

You’ll find this everyday pottery comprises 60-65% of assemblages at habitation sites.

Polychrome Pottery emerges later, with Sikyatki’s distinctive yellow from coal-firing and Four Mile’s red-white slips with black glaze paint (1325-1400 AD), demonstrating technological advancement and trade networks. Jeddito Yellow Ware, produced from 1300-1625, features manganese-based paint that fires brown to black with asymmetrical patterns on both surfaces. Artisans applied decorative elements using Yucca plant fibers as paintbrushes, working freehand on curved surfaces to achieve their sophisticated designs.

Ancient Artistic Methods and Design Techniques

You’ll observe that Anasazi potters executed geometric and naturalistic designs through freehand painting, utilizing yucca fiber brushes to apply mineral and organic pigments directly onto vessel surfaces.

The artists achieved precise symmetry by rotating coil-built forms while painting repeated motifs—spirals, stepped patterns, and linear elements—designed for viewing from multiple angles.

These techniques required skilled hand-eye coordination to maintain design continuity across curved surfaces, particularly evident in black-on-white slip decorated wares and polychrome vessels that combined contrasting pigment applications. The decoration styles embodied horror vacui principles, with artists filling available space while creating interplay between negative and positive areas. Potters also created distinctive yellow pottery near Hopi Pueblos using local clay that was fired at high temperatures, producing durable vessels that were traded widely throughout Anasazi territories.

Freehand Painting on Pottery

The Anasazi potters developed sophisticated freehand painting techniques that required precise coordination of materials, tools, and surface preparation to achieve their distinctive black-on-white ceramics.

You’ll find these freehand techniques relied on meticulously smoothed surfaces, created by polishing dried pottery with stones before applying white clay slip. This preparation enabled potters to execute straight lines and complex geometric patterns directly onto unfired vessels using yucca fiber brushes.

Essential Components of Pottery Aesthetics:

- Plant-derived pigments from boiled Rocky Mountain bee plant or beeweed created deep black contrast

- Frequent brush washing maintained precision in line work and prevented paint builment buildup

- Varied application methods including stippling, sgraffito, washes, and spattering produced dimensional effects

The potters achieved visual depth by applying dense paint in design centers that gradually lightened outward, demonstrating masterful control over their medium. Decoration was applied with mineral or plant-based paints before the pottery underwent the firing process. Many designs incorporated a line break, an intentional gap in the painted pattern that held spiritual significance in ancestral Pueblo pottery traditions.

Symmetry in Vessel Design

Mathematical precision governed Anasazi vessel decoration through deliberate application of symmetry principles that evolved considerably across seven distinct chronological periods.

You’ll observe reflective symmetry mirroring designs across central axes, while rotational symmetry repeats elements around fixed points. Early periods (AD 625-795) mainly featured C2 and D2 symmetries, shifting to p112 dominance through AD 1175.

Post-1175 witnessed increased asymmetric C1 patterns and finite mirror reflection arrangements. Virgin Anasazi ceramics demonstrate glide, bilateral, and rotational configurations.

Chaco Black-on-white employed limited two-dimensional symmetries within hatched patterns, contrasting with Gallup Black-on-white’s continuous-line construction. Identical patterns found at Pueblo Bonito and other San Juan Basin sites indicate sociopolitical connections among communities during the Chaco network peak.

You’ll find designers utilized negative space reserves, internal hatching, and bounding lines to enhance symmetrical arrangements. These pattern shifts correlate directly with cultural transformations around AD 800-900 and post-1175.

Pigments and Yucca Brushes

Ancient Anasazi artisans systematically exploited diverse mineral resources to create a sophisticated pigment palette spanning black, red, blue, and green hues.

You’ll find black clay on stone carvings, red hematite on artifacts, blue azurite in art pieces, and malachite-based greens on ancient darts. The pigment composition varied considerably between regions—Tularosa pottery featured mineral-based paints while Mesa Verde utilized organic compounds.

Key Brush Techniques:

- Yucca brushes applied paints on plastered surfaces, often used alongside hands for detailed artwork

- Natural brush materials from local resources enabled precise cave wall paintings

- Pestles and bowls ground pigments with cobblestones before application

You’ll discover over 60 plaster layers in some rooms, with black soot marking distinct phases.

Chemical analysis of weaponry pigments reveals standardized color recipes, demonstrating sophisticated knowledge transmission across communities. The technique of smothered organic paint firing created distinctive finishes on Mesa Verde black-on-white pottery produced until 1300 AD. Archeologists studying these plaster compositions can determine the soil sources used by Ancestral Puebloan people, revealing trade patterns and resource management practices across different settlements.

Functional Purposes of Anasazi Ceramics and Objects

Anasazi ceramic assemblages reveal distinct functional categories differentiated by manufacturing techniques, surface treatments, and firing temperatures.

You’ll observe that 35-40% of site pottery consisted of decorated fine wares designated for ceremonial contexts and intercommunity exchange, while corrugated and plain gray vessels served quotidian cooking and storage needs.

The archaeological record demonstrates that utilitarian corrugated jars, formed by leaving coils unsmoothed, provided superior thermal properties for boiling compared to plain pottery, whereas narrow-necked vessels and aboveground chambers functioned as liquid storage systems.

Tall cylindrical vessels found throughout the region are generally considered ceremonial vessels, distinguished by their unique form factor and specialized decorative treatments.

Ceremonial and Trade Vessels

Ceramic vessels recovered from Anasazi sites reveal distinct functional categories, with decorated fine wares serving ceremonial purposes separate from utilitarian cooking and storage vessels.

You’ll find ritual bowls featuring intentional holes—termed “killed bowls”—punctured during funerary ceremonies to release spirits into the afterlife. Effigy vessels, representing the northernmost examples of Mesoamerican influence, served shamanic practices and burial offerings.

Women applied freehand painted designs using yucca fibers, creating black-on-white patterns that transmitted cultural knowledge across generations.

Archaeological evidence indicates:

- Decorated pottery comprised 35-40% of site assemblages, demonstrating significant ritual investment

- Four Mile Polychrome jars (1325-1400 CE) represented peak ceramic trade art in regional exchange networks

- Turquoise, jet, and shell inlays accompanied ceremonial vessels in burial contexts like Chaco Canyon Room 33

Household and Cooking Implements

Beyond their ritual significance, Anasazi pottery fulfilled essential domestic functions that defined daily subsistence patterns across the Colorado Plateau.

You’ll find corrugated jars served as primary cooking vessels, their unsmoothed coil textures providing thermal shock resistance during repeated heating cycles. These household utensils rested directly on hearth sandstone slabs alongside metates and manos for corn grinding.

Cooking techniques evolved from early basketry methods—where pitch-lined containers held water heated by stone-dropping—to direct-fire ceramic applications post-AD 550.

Yellow clay ladles from Hopi regions facilitated stew preparation, while bone awls and digging sticks supported food processing activities.

Archaeological evidence reveals two daily meals of cornbread and stew, prepared using wild plants like saltbush and juniper berries.

Macrobotanical remains confirm cheno-am and prickly pear supplemented maize-based diets across pithouse settlements.

Trade Routes and Distribution Across North America

Between 900 and 1300 CE, elaborate road systems traversed the Four Corners region, connecting southeastern Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico through formally engineered pedestrian thoroughfares that converged at Chaco Canyon.

These trade networks facilitated cultural exchanges across the Greater Southwest, extending to Mesoamerica and the Gulf of California.

Archaeological evidence reveals the scope of these routes:

- One million turquoise pieces recovered from sites demonstrate extensive procurement patterns, with hydrogen and copper isotopic signatures tracing sources from western deposits.

- Obsidian and Pacific shells moved bidirectionally between inland pueblos and coastal tribes.

- Macaw feathers, imported timber, and distinctive pottery linked Chacoan sites to Mesoamerican civilizations like the Toltec Empire.

Post-1200 collapse, Rio Grande pueblos maintained exchanges with Plains tribes, trading agricultural surplus for buffalo products and salt.

Museums and Sites Housing Anasazi Collections

Since the early 20th century, institutions across North America have systematically assembled extensive collections of Ancestral Puebloan material culture, preserving over 150,000 catalogued artifacts that document technological innovations, subsistence strategies, and sociocultural complexity from approximately 100 BCE to 1300 CE.

Over 150,000 Ancestral Puebloan artifacts chronicle thirteen centuries of technological advancement and cultural development across institutional collections.

You’ll find significant holdings at Arizona State Museum‘s Four Mile Polychrome ceramics and Indian Arts and Culture’s 75,000-object repository in Santa Fe.

Edge of the Cedars State Park maintains the Four Corners’ largest pottery assemblage, while Anasazi State Park Museum offers direct access to excavated materials from the Coombs Site occupation (1050-1200 CE).

Museum accessibility includes virtual tours and life-sized architectural replicas.

However, NAGPRA compliance since 1990 has mandated repatriation protocols, fundamentally reshaping artifact preservation practices and institutional custodianship across participating repositories.

Rock Art, Basketry, and Non-Ceramic Creations

Ancestral Puebloan communities developed sophisticated non-ceramic material traditions that’ve proven remarkably resilient across the archaeological record, with rock art serving as the most visible and geographically widespread form of cultural expression from approximately 1000 BCE to 1540 CE.

You’ll find rock art techniques employed pecking and incising methods using agate, chert, or jasper tools to create permanent imagery on sandstone surfaces. These symbolic motifs include anthropomorphs with trapezoidal torsos, zoomorphs depicting bighorn sheep and pronghorn antelope, and spiral designs marking celestial movements.

Notable Rock Art Concentrations:

- Chaco Canyon, New Mexico – Fajada Gap panels featuring anthropomorphs, zoomorphs, and astronomical symbols

- Canyonlands Needles District, Utah – Archaic Portrait Gallery with 2000-year-old figures and “Many Hands” panels

- Monument Valley – Eye of the Sun Arch displaying hunting narratives and shamanic imagery

Frequently Asked Questions

What Legal Permits Are Required to Search for Anasazi Artifacts?

You’ll need ARPA permits for federal lands, Class C/Type 1 permits plus separate ARPA authorization for Navajo territories, and state-specific permits for public lands. Permit requirements and legal regulations vary by jurisdiction, protecting cultural resources while enabling authorized research.

Which Modern Locations Offer the Best Artifact Discovery Opportunities?

You can’t legally collect artifacts at Mesa Verde, Canyon de Chelly, Chaco Canyon, or Hovenweep National Park. These sites prioritize Ancestral Puebloan artifact preservation through federal protection, restricting personal discovery while enabling professional archaeological research only.

How Can Collectors Distinguish Authentic Anasazi Pieces From Replicas?

You’ll identify authentic pieces through scientific testing—carbon dating, residue analysis, and pollen verification—while identifying fakes by examining preservation techniques like modern kiln firing, manganese paints, restoration fills, and suspiciously pristine conditions unlike genuinely weathered artifacts.

What Is the Estimated Monetary Value of Different Artifact Types?

Artifact valuation ranges from $40 for arrowheads to $8,500 for premium canteens, with market demand driving pottery prices between $450-$1,750. You’ll find bowls, jars, and effigies commanding mid-range values based on condition and provenance documentation.

Are There Ethical Concerns About Removing Artifacts From Original Sites?

Yes, you’ll face significant ethical concerns. Removing artifacts destroys cultural preservation and historical significance by eliminating archaeological context, violating federal laws like NAGPRA, disrespecting descendant communities, and permanently compromising scientific research potential for understanding past societies.

References

- https://ancientpottery.how/anasazi-art/

- https://universe.byu.edu/2006/11/14/anasazi-pottery-merges-beauty-in-form-and-function/

- https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/a/Anasazi.shtml

- https://www.davisart.com/blogs/curators-corner/native-american-heritage-month-the-anasazi/

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/the-anasazi-tribe-pottery-homes-ruins-clothing.html

- https://crowcanyon.org/ResearchReports/CastleRock/Text/crpw_glossary.php

- https://ehrafarchaeology.yale.edu/traditions/nt95/summary

- http://www.clayhound.us/sites/anasazi.htm

- https://app.fiveable.me/key-terms/native-american-history/anasazi-pottery

- https://ceramics.nmarchaeology.org/typology/culture?p=1