You’ll identify old structure foundations by examining visible masonry patterns, material composition, and width measurements—stone foundations typically measure 22–24 inches and predate 1915, while brick foundations show characteristic bonding patterns from the 19th century. Look for diagonal cracks, bowing walls, and gaps between baseboards as evidence of settlement or movement. Check construction records and conduct exterior inspections to determine foundation type, noting spalling, deteriorated mortar joints, and early concrete’s distinctive aggregate composition. Professional assessment methods including GPR, penetrometers, and settlement monitoring will reveal subsurface conditions and progressive damage patterns requiring intervention.

Key Takeaways

- Stone foundations (granite, limestone, sandstone) were typical before 1915, usually 22–24 inches wide in rubble trench configurations.

- Brick foundations gained popularity in the 19th century, using running, common, or Flemson bonds; vulnerable to spalling and crumbling mortar.

- Early concrete foundations show aging patterns, aggregate composition, formwork impressions, and hydraulic lime mixtures with possible steel bar reinforcement.

- Conduct exterior inspections for cracks and deterioration; review historical records and permits to determine foundation type and construction era.

- Ground Penetrating Radar and visual examination of accessible elements help identify foundation materials without invasive excavation.

Visual Warning Signs of Foundation Problems

Visual assessment of structural components provides the primary diagnostic method for detecting foundation deterioration in existing buildings.

Visual inspection remains the essential first-line approach for identifying foundation damage and structural deterioration in older residential and commercial structures.

You’ll identify compromised soil stability through diagonal or stair-step cracks in masonry, horizontal fissures indicating subsidence, and separations exceeding 1/8 inch.

Monitor crack progression systematically—expanding gaps denote active settlement.

Examine floor levelness using precision instruments; sloping surfaces reveal differential movement from inadequate waterproofing techniques allowing moisture infiltration.

Document door and window operability—sticking mechanisms and frame misalignment confirm structural displacement.

Inspect for gaps between baseboards, crown molding, and wall intersections; these separations indicate ongoing foundation shifts.

Basement walls exhibiting bowing or bulging require immediate evaluation; these deformations result from hydrostatic pressure when waterproofing techniques fail.

Nails popping out from drywall surfaces signal framing displacement caused by foundation movement.

Assess crawl spaces and basements for standing water or dampness unrelated to plumbing fixtures, as moisture buildup accelerates foundation degradation and support weakening.

Catalogue all observations with measurements, dates, and photographic evidence for comparative analysis.

Common Foundation Types in Historic Buildings

When examining historic buildings, you’ll primarily encounter stone and brick foundation systems that dominated construction from the 1800s through the early 1900s.

Stone foundations typically feature granite, limestone, sandstone, or marble set in rubble trench configurations with loose stones forming perimeter walls.

While brick foundations became prevalent in 19th-century construction using various bonds including running, common, and Flemson patterns.

Early concrete construction methods emerged as interim technology, introducing slab-on-grade systems with thickened edges and pier-and-beam configurations that preceded modern poured foundation techniques. These foundations became popular post-1900 with the development of improved Portland cement formulations. Ancient civilizations like Egypt and Rome established foundational principles using limestone blocks and concrete that continue to influence these historic foundation designs.

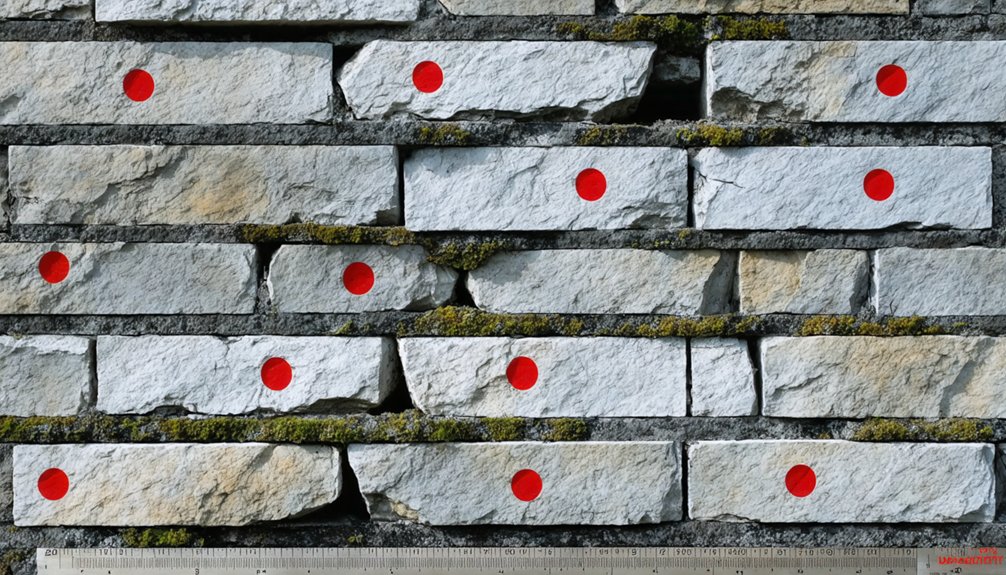

Stone and Brick Foundations

Historic buildings constructed before 1915 mainly feature stone foundations, with limestone, sandstone, and field or river stones serving as primary materials. You’ll find these structural walls measuring 22–24 inches wide at foundation levels, constructed from materials you can identify by scratching softer varieties with a screwdriver.

Brick foundations gained prevalence during the 19th century, offering uniform stacking capabilities and modern aesthetics while maintaining necessary breathability—though insufficient for handling contemporary groundwater pressure without proper drainage techniques. The thickness of brick foundations is measured in wythes, or layers, of individual bricks stacked to achieve structural stability.

When evaluating these systems, you’ll encounter common deterioration patterns: spalling brick surfaces, bulging walls from soil pressure, and crumbling mortar joints. Foundation insulation wasn’t historically incorporated, as builders prioritized structural integrity over thermal performance.

Understanding these construction methods enables you to make informed preservation decisions aligned with original building practices.

Early Concrete Construction Methods

Although ancient civilizations developed concrete millennia before modern construction, the material’s application in residential foundations didn’t achieve widespread adoption until the early 20th century. You’ll identify historic construction phases by examining concrete aging patterns and composition.

Early examples from 3000 B.C. used gypsum-lime mortars, while Romans perfected pozzolan-based mixtures with volcanic ash. Portland cement’s 1824 development revolutionized foundation work, though residential use remained limited until Gustav Stickley’s 1912 catalogs popularized poured foundations.

You’ll find these systems featured excavated trenches, rebar-reinforced footings, and two-sided wooden formwork containing successive concrete pours. Post-WWII housing booms accelerated monolithic slab adoption for speed and economy. Modern foundations incorporate steel bars and mesh to resist soil shifts and environmental stresses that can compromise structural integrity.

When documenting older structures, note aggregate types—travertite in lower courses, lighter pumice above—and formwork impressions indicating construction methodology. John Smeaton’s 18th-century work with hydraulic lime demonstrated how combining lime with brick and pebbles could create durable foundations, as proven by the Eddystone Lighthouse built in 1759.

Initial Assessment and Documentation Techniques

Before undertaking any invasive testing or structural intervention, you must establish a thorough baseline understanding of the foundation’s current condition through systematic visual inspection and documentation review.

Begin by examining accessible exterior foundation walls for cracks, spalling concrete, and material deterioration.

Identify the foundation type through visible characteristics—basement windows, crawl space vents, or slab-on-grade features.

Document water intrusion evidence, as moisture protection deficiencies accelerate structural degradation.

Review historical records, including original building plans, property inspection reports, and previous foundation reinforcement attempts.

Categorize defects by severity: immediate repair needs versus progressive damage potential.

Note inaccessible areas behind finished walls or stored materials that may conceal critical issues.

Look for evidence of settlement, particularly checking whether footings exist under walls, as older construction often proceeded without proper foundation support.

This preliminary assessment determines whether detailed structural analysis or specialized testing is necessary.

Professional Diagnostic Equipment and Testing

Settlement monitoring equipment enables you to track foundation movements with precision through wireless sensors, inclinometers, and tilt meters that capture both immediate and long-term displacement patterns.

Subsurface investigation tools, including Ground Penetrating Radar and the GeoScope™ GPR system, allow you to map foundation depth, identify voids, and detect underground utilities without excavation.

When you combine penetrometers, Standard Penetration Tests (SPT), and Cone Penetration Tests (CPT) with continuous monitoring data, you’ll establish exhaustive bearing capacity profiles and document soil conditions affecting foundation stability. Settlement plates installed with riser pipes provide cost-effective surface-level readings for tracking vertical displacement in older foundations. Thermal imaging cameras reveal temperature variations that indicate hidden moisture intrusion and structural anomalies within aging foundation materials.

Settlement Monitoring Equipment

How do professionals accurately measure and track foundation movement over time? Settlement monitoring equipment provides the empirical data you’ll need to assess structural integrity independently.

Settlement plates—steel platforms installed at various soil depths—enable precise vertical displacement tracking through periodic surveying against established reference points.

Inclinometer methods detect lateral movement and tilting by measuring probe positions within installed tubes.

You’ll find these core technologies essential:

- Extensometers measuring subsurface compaction and expansion at multiple depths

- Wireless settlement gauges delivering real-time displacement data via telemetry

- Hydrostatic level cells detecting differential settlement across foundation spans

- Tiltmeters monitoring structural rotation with millimeter-level accuracy

This instrumentation network offers autonomous verification of foundation conditions, eliminating reliance on subjective assessments while providing quantifiable evidence of ground movement patterns.

Subsurface Investigation Tools

What lies beneath an existing foundation often determines its long-term viability, making subsurface investigation tools indispensable for all-encompassing structural assessment. Ground Penetrating Radar enables geophysical mapping without excavation, detecting voids, utilities, and soil density variations through electromagnetic pulses.

Seismic Refraction Surveys measure wave velocities to reveal bedrock depth and weak zones. Electrical Resistivity Tomography maps groundwater levels and contamination patterns via resistance measurements.

When you need direct verification, Cone Penetration Testing delivers continuous soil response logs efficiently, though it’s often paired with borehole sampling since it doesn’t retrieve specimens. Standard Penetration Tests and California Samplers extract undisturbed cores for laboratory analysis.

Flat Plate Dilatometer Tests measure lateral stress and stiffness in-situ. Deploy multiple methods simultaneously—integrating non-invasive geophysics with targeted sampling yields the most reliable foundation characterization data.

How Foundations Change Over Time

- Initial settling from poor compaction causes minor cracks and floor slope.

- Moisture infiltration weakens porous materials through freeze-thaw expansion.

- Hydrostatic pressure accumulates from drainage failures, bowing walls outward.

- Material degradation accelerates as mortar erodes and unreinforced elements become brittle.

Environmental factors—tree root intrusion, seismic shifts, erosion—compound these baseline processes.

You’ll observe progressive symptoms: widening cracks, misaligned openings, visible wall displacement.

Without intervention, cumulative damage threatens structural integrity and occupant safety.

Materials and Construction Methods by Era

When you examine foundation materials across civilizations, you’ll find construction methods evolved in direct response to available resources and environmental demands.

Ancient Egyptians employed sun-baked adobe and limestone blocks directly on bedrock, while Romans innovated pozzolana-lime concrete for underwater applications.

Pre-industrial builders utilized composite pile systems and rediscovered hydraulic lime by 1759, enabling foundation retrofitting of coastal structures.

The mid-1800s industrial revolution standardized materials through steam-powered production, yielding uniform bricks and quarried stone.

By 1878, regulations mandated 225mm Portland cement concrete under footings.

Early 20th-century construction embraced reinforced concrete slabs and raft foundations for rapid deployment.

Understanding these era-specific techniques informs material conservation strategies, allowing you to authenticate construction periods and assess structural integrity based on documented building practices.

Monitoring Structural Movement Patterns

As foundations age and environmental conditions shift, systematic monitoring reveals movement patterns that indicate structural stability or deterioration. You’ll need to establish baseline measurements through reference points and redundant networks that track both horizontal and vertical displacement.

Soil composition directly influences settlement rates, while thermal expansion creates seasonal fluctuations in structural dimensions.

Settlement patterns emerge from complex interactions between subsurface conditions and temperature-driven expansion cycles affecting structural performance.

Deploy these monitoring technologies to capture exhaustive movement data:

- Tiltmeters and prisms detect wall inclination and settlement during renovations

- Automated settlement profilers identify differential movement across floor systems

- GNSS receivers provide millimeter-level accuracy in remote foundation locations

- Horizontal shape arrays track subsurface deformation beneath highways and tank foundations

Correlate vibration data with crack meter readings to distinguish between benign seasonal shifts and progressive structural deterioration requiring intervention.

When Repairs Become Necessary

Movement data collected through systematic monitoring provides the quantitative basis for repair decisions, but specific physical indicators determine when intervention can’t be delayed.

You’ll need foundation reinforcement when cracks exceed 1/4 inch in block walls or when water seepage accompanies structural displacement.

Historical construction techniques like beam and pier systems show distress through sagging floors and squeaking, while bowing basement walls from soil pressure require steel reinforcement to prevent complete rebuilding.

Professional evaluation costs average $600, with typical repairs totaling $5,074.

Don’t postpone action when you observe gaps between foundation walls and sill plates, chimney separations, or sudden floor unevenness across large areas.

Early intervention prevents escalation to $20,000-$100,000 replacement costs, preserving your property’s structural integrity and your financial autonomy.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Much Does a Professional Foundation Inspection Typically Cost for Older Homes?

You’ll typically pay $300–$1,000 for professional foundation inspections on older homes, with costs increasing when foundation settlement or water seepage requires extended evaluation time, specialized testing, and detailed documentation of deteriorated conditions affecting structural integrity.

Can Historic Foundation Materials Contain Hazardous Substances Like Asbestos or Lead?

Yes, you’ll find hazardous substances in historic foundations. Material degradation releases asbestos from cement, lead from paints, and heavy metals from coal ash fill. Professional detection techniques using XRF analyzers and laboratory sampling guarantee your safe remediation planning.

Do Foundation Repairs Affect a Historic Building’s Eligibility for Preservation Tax Credits?

Foundation repairs don’t disqualify your building from historic preservation tax credits if they maintain structural integrity and meet the Secretary’s Standards. You’ll need to document all work through Parts 2 and 3 applications, ensuring repairs preserve historic character features.

What Permits Are Required Before Starting Foundation Repair Work on Old Structures?

Like scaffolding supporting restoration, you’ll need structural permits for foundation work. Building code compliance requires engineering plans, structural integrity assessment reports, and excavation permits. Your contractor submits calculations to local authorities, ensuring your property rights remain protected through proper documentation.

How Does Foundation Type Impact Home Insurance Rates for Historic Properties?

Foundation type directly affects your insurance rates by altering reconstruction cost estimates by approximately 18%. Insurers assess foundation settlement risk and moisture damage potential, with crawl spaces and pier systems requiring different coverage levels than standard slab foundations.

References

- https://foundationrepairsecrets.com/old-vs-new-how-structural-age-influences-foundation-inspection-and-repair/

- https://xpertfoundationrepair.com/how-foundation-problems-are-diagnosed-with-plates-sensors-and-more/

- https://goldenbayfoundationbuilders.com/old-house-foundation-types/

- https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS4219

- http://www.sedhc.es/biblioteca/actas/CIHC1_093_Garc__a A.pdf

- https://www.exactusengineering.com/resources/foundation-cracks-homes-buildings

- https://cr1981.com/identifying-and-addressing-hidden-structural-damage-in-historic-homes/

- https://fcsfoundationandconcrete.com/understanding-historical-home-foundation-repair-a-restoration-guide/

- https://relishrealty.com/real-estate-blog/how-to-identify-foundation-problems-in-older-homes/

- https://foundationsunlimited.com/early-warning-signs-of-foundation-problems/