You’re looking in the wrong state—Gold Hill Mining District sits in Rowan County, North Carolina, not South Carolina. Discovered in 1824, it became America’s first organized mining operation, with the Barnhardt Shaft reaching 435 feet by 1842 and the Randolph Mine hitting 850 feet in 1843. The district produced $6-9 million in gold from quartz veins averaging 2-15 feet wide, with high-grade ore samples reaching 19 oz/ton. The complete stratigraphic profile and engineering innovations that enabled these pioneering extraction depths reveal fascinating geological insights.

Key Takeaways

- Gold Hill Mining District is located in Rowan County, North Carolina, not South Carolina, near the state border.

- The district produced $6-9 million in gold from 1842-1915, with high-grade ore reaching 19 ounces per ton.

- Sixteen to twenty-three shafts accessed quartz veins 2-15 feet wide, with depths reaching 850 feet by 1843.

- Mining operations ceased by 1915 due to narrowed veins, increased costs, and inefficient processing methods reducing profitability.

- Gold Hill Mines Historic Park now preserves the district’s vertical shafts, ruins, and geological features for education.

America’s First Gold Rush: The 1824 Discovery

When did America’s gold mining industry truly begin? You’ll find the answer in North Carolina’s 1824 Gold Hill discovery in Rowan County, following an 1823 geological survey that predicted auriferous deposits.

This marked the critical shift from Reed’s 1799 placer findings to systematic mineral exploration. While gold panning dominated early extraction methods in creek beds, 1824 established the Gold Hill Mining District as America’s first organized mining operation.

The Randolph Mine eventually reached 850 feet depth, with the Barnhardt extending 435 feet. You’re looking at approximately six million dollars in pure gold extracted from this single district—one-third from the Randolph Shaft alone.

This discovery catalyzed North Carolina’s dominance in American gold production until California’s 1848 strike, fundamentally transforming your nation’s mineral economy. By the 1830s, gold mining in the Carolinas had become second in economic importance to agriculture alone. The region’s productive output prompted the construction of the Charlotte Mint, which opened in July 1837 to process the substantial gold deposits from local mines.

Establishing a Mining Boomtown in 1843

By 1843, you’re witnessing the transformation of a mining camp into an incorporated municipality with 3,000 residents. The town’s infrastructure expanded to accommodate 23 operational mines in the district, establishing a mile-long commercial corridor hosting 16 merchants, 23 saloons, and multiple lodging facilities.

This administrative shift coincided with the sinking of the Barnhardt shaft to 435 feet in 1842 and the Earnhardt mine to 850 feet in February 1843—the latter becoming the Randolph mine with ore veins measuring 2-15 feet in width. The combined output of these operations would eventually yield $7-9 million before the California gold strike redirected national attention westward.

The formalization of the town’s governance occurred when Col. George Barnhardt assumed the first mayoral office. The settlement joined other geographical locations across the United States that shared the Gold Hill name, reflecting the common practice of naming mining communities after their primary mineral resource.

Town Incorporation and Leadership

Following nearly two decades of gold extraction that began with the 1824 discoveries, Gold Hill achieved formal incorporation in 1843 as Rowan County’s first mining boomtown.

You’ll find that town governance emerged through a structured meeting establishing administrative protocols for the burgeoning community. Col. George Barnhardt, son-in-law of Reed Gold Mine’s founder, secured the first mayoral position. His leadership coordinated the Barnhardt Gold Mine’s vertical shaft development, reaching 435 feet depth into a 20-foot-wide auriferous quartz vein extending 1,500 feet laterally.

The district’s mining equipment infrastructure supported twenty-three operational shafts, yielding six million dollars pre-Civil War. This organizational framework enabled systematic extraction from paired operations—Barnhardt’s facility and the Earnhardt/Randolph Mine at 850 feet—establishing Gold Hill as the South’s premier gold-producing district before California’s 1849 rush. The region’s prosperity prompted construction of a federal mint in Charlotte to process the extracted precious metals. Copper mining continued within the district, sustaining industrial operations until 1907 when extraction activities ultimately ceased.

Rapid Population Growth

As the Barnhardt shaft penetrated 435 feet into auriferous quartz in 1842 and the Randolph/Earnhardt operation reached 850 feet by 1843, Gold Hill’s population surged to 3,000 residents within the incorporation year.

You’ll find this mineral exploration boom transformed a modest mining camp into North Carolina’s richest gold district east of the Mississippi. The demographic shift drew miners, entrepreneurs, and skilled managers from northeastern states and Europe—men seeking fortune beyond regulatory constraints. These early operations relied on rudimentary, poorly functioning machinery that reflected the primitive technological state of the district’s formative years.

Infrastructure and Commerce Boom

Upon incorporation in 1843, Gold Hill transformed into North Carolina’s most sophisticated mining settlement, with Col. George Barnhardt—connected to the Reed Gold Mine family—elected as first mayor.

You’ll find the district’s mining equipment represented cutting-edge technology: the Barnhardt shaft (1842) descended 435 feet as the first vertical shaft east of the Mississippi, while the Randolph shaft reached 800-850 feet, becoming the region’s deepest operation.

The infrastructure supported 3,000 residents across a mile-long main street featuring sixteen merchants, twenty-three saloons, two hotels, and one boarding house.

Labor conditions drove this rapid expansion, with twenty-three active mines producing six to nine million dollars in gold—sufficient output to justify Charlotte’s federal mint construction, though inefficient extraction methods squandered considerably more value underground.

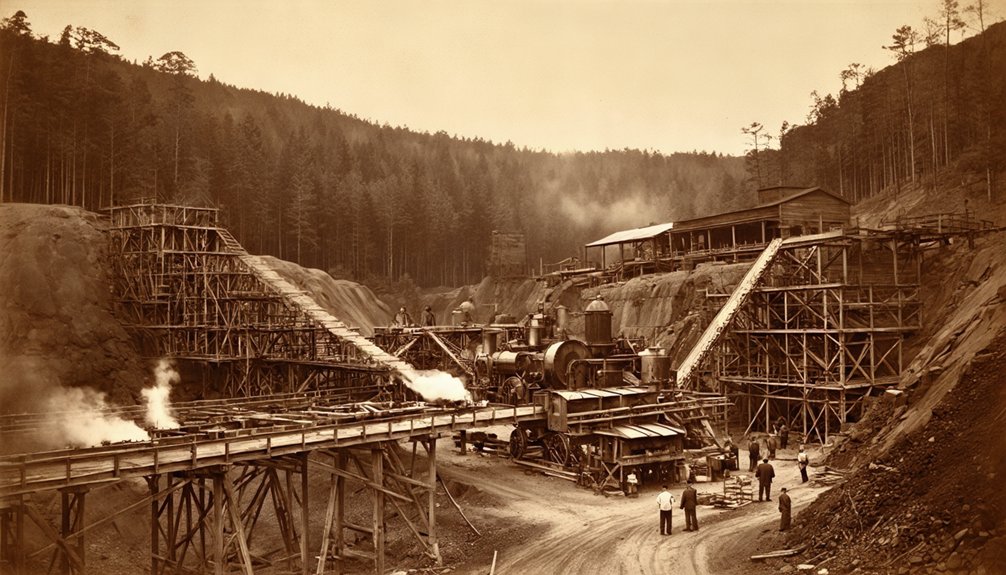

The Barnhardt and Randolph Shafts: Engineering Marvels of Their Time

The Barnhardt Shaft‘s 435-foot vertical descent in 1842 established it as the first and deepest eastern U.S. mine shaft, accessing a 20-foot-wide quartz vein that extended 1,500 feet horizontally beneath Gold Hill’s main street.

You’ll find the Randolph Shaft, opened in 1843 across the street, doubled that achievement at 800-850 feet deep while exploiting veins 2-15 feet wide that yielded up to 19 ounces per ton.

These two operations alone extracted an estimated $6 million in pre-Civil War gold, with the Randolph producing one-third of Gold Hill’s total output.

It continued production through 1914-15 with documented recoveries of 3,877 ounces from a single vein.

The Randolph’s underground workings featured seven interconnected shafts accessing three major veins, with 70 meters of drifts developed along the ore bodies.

The district’s mineral wealth extended beyond these flagship operations to include the Miller Shaft, Honeycutt Mine, Troutman Mine, Union Copper Mine, and Barringer Mine, all discovered between 1842-1844.

Unprecedented Depth and Scale

When Col. George Barnhardt opened his shaft in 1842, you’re witnessing American mining history being written in real-time. His 435-foot vertical descent claimed the national record for deepest shaft, revealing geological formations that widened to a 20-foot quartz vein laced with gold.

You’ll find the tunnel extended 1,500 feet beneath Gold Hill’s main street—an audacious engineering feat for independent operators.

Across the street, the Randolph shaft shattered Barnhardt’s record by 1843, plunging 850 feet to become America’s deepest gold mine. You’re looking at mineral deposits yielding up to 19 ounces per ton in upper levels, with the Randolph vein spanning 2-15 feet wide.

These weren’t corporate ventures—they were privately-funded operations that outperformed anything east of the Mississippi, proving what determined prospectors could achieve without government oversight. Together, the Barnhardt and Randolph mines became the most productive operations east of the Mississippi during the gold rush era.

Combined Production and Legacy

Between 1842 and 1915, Barnhardt and Randolph shafts generated an estimated $6 million in pure gold from Gold Hill’s quartz veins—a production volume that dominated Eastern American mining operations.

You’ll find the Randolph vein’s 2-to-15-foot width delivered samples ranging from ½ to 19 ounces per ton in upper levels.

Barnhardt’s 435-foot depth accessed a 20-foot-wide quartz structure extending 1,500 feet beneath the main street.

The 1914-15 ore extraction processed 7,250 tons, yielding 3,877 ounces of gold through mineral processing operations.

This production sparked Charlotte’s federal mint construction and sustained 23 district mines by 1843.

Though inefficient methods lost substantial value, these operations established Gold Hill’s reputation as the premier mining district east of the Mississippi.

Production Records That Outshone the East

Before California’s 1849 gold rush transformed American mining, North Carolina’s Gold Hill district had already established itself as the eastern United States’ most productive gold operation, generating an estimated six million dollars in pure gold from its ore bodies.

You’ll find the Randolph Shaft reached 820 feet—one of the South’s deepest excavations—while the Barnhardt Shaft exceeded 400 feet as the first vertical shaft east of the Mississippi.

The regional geology produced veins ranging from 2 to 15 feet in width, with ore samples yielding between ½ ounce to 19 ounces per ton.

This dominance prompted federal mint construction in Charlotte, recognizing how advanced mining technology and systematic extraction methods gave you access to unprecedented eastern wealth reserves.

Life in a Frontier Mining Camp

By 1843, Gold Hill’s transformation into an incorporated municipality reflected its emergence as one of North Carolina’s most concentrated commercial centers.

Gold Hill emerged as a densely concentrated commercial hub, its 1843 incorporation marking a pivotal shift in North Carolina’s economic landscape.

Where twenty-three saloons and sixteen merchants served a continuously rotating workforce across three daily mining shifts.

You’ll find that mining technology investments from New York exchange trading created distinct social hierarchy layers—mine experts and investors occupied the two-story administrative office while immigrant laborers rotated through underground operations.

The town’s infrastructure supported approximately six brothels, two hotels, and a boarding house along its one-mile main street.

Charlotte’s mayor openly envied this prosperity, where employment opportunities beyond agriculture attracted North Carolina’s largest non-farming workforce.

Capital flowing from Northern and international sources established Gold Hill as a genuinely autonomous frontier economy operating outside traditional agricultural constraints.

International Investment and Edison’s Involvement

Gold Hill’s prosperity collapsed during the Civil War, but London financiers recognized the district’s untapped potential when New Gold Hill Ltd. established operations in the 1880s. This international investment brought foreign capital that transformed extraction capabilities through progressive methods you’d find impressive even today. The company employed top scientists, including Thomas Edison, whose Edison innovations targeted deep-vein access—the Randolph shaft reached 820 feet, representing one of America’s earliest vertical operations.

These technological advances paid off: operations matched previous-era outputs for twenty years, contributing to the district’s estimated $1.65 million production through 1915. During the final 1914-1915 period, miners processed 7,250 tons, recovering 3,877 ounces of gold from the north vein before economic factors shuttered operations permanently.

The Decline of Mining Operations

The Civil War’s onset in 1861 disrupted North Carolina’s gold mining infrastructure when state militia seized the Charlotte mint, effectively severing the industry’s monetary circulation system. You’ll find employment plummeted as Gold Hill’s boom status collapsed.

The 1880s London-backed Gold Hill Ltd. Mining Co. briefly revived operations, pushing shafts to unprecedented depths—Randolph reached 820 feet, among the South’s deepest. Despite progressive extraction methods and $6-9 million in total production, inefficient processing lost substantial gold.

Mining regulations and labor disputes compounded operational challenges as veins narrowed from 2-15 feet width. The richest upper levels yielded ½-19 oz/ton, but by 1915, after processing 7,250 tons for merely 3,877 oz gold, economic viability collapsed.

Exploration attempts in 1950 confirmed what operators suspected: extraction costs permanently exceeded returns.

Legacy and Economic Impact on North Carolina

North Carolina’s 1799 gold discovery transformed western regions into America’s first commercial mining frontier, establishing economic patterns that persisted through the antebellum period.

You’ll find gold mining became the state’s second-largest economic driver, generating six million dollars from Gold Hill alone and prompting federal mint construction in Charlotte.

The industry’s wealth creation established Charlotte’s banking dominance while attracting English engineers whose cultural influences shaped operational practices across 23 consolidated mines.

Mining infrastructure directed settlement patterns throughout piedmont and Appalachian foothills, employing over 900 workers at peak operations.

However, environmental consequences from extraction methods remain underexamined.

The sector’s technological innovations attracted leading scientists like Edison, though revival attempts using progressive techniques couldn’t sustain long-term profitability beyond copper operations.

Visiting Gold Hill Mines Historic Park Today

Located along US 52 in Rowan County, Historic Gold Hill presents visitors with a preserved nineteenth-century mining landscape where vertical shaft technology reached unprecedented eastern depths. You’ll explore a mile-long main street featuring restored merchants’ buildings, saloons, and mining offices that document operations spanning 1824 to 1915.

The Barnhardt Mine’s 435-foot shaft—America’s first vertical mine east of the Mississippi—and the Randolph Mine’s 800-850 foot depth showcase advanced extraction methods. Mining equipment displays illustrate techniques that recovered veins ranging 2 to 15 feet wide, yielding up to 19 ounces per ton.

Geological formations visible throughout the site reveal the copper-bearing strata that sustained operations beyond gold’s decline. The Historic Gold Hill and Mines Foundation manages interpretive programming detailing this $6 million production legacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Mining Techniques Were Used to Extract Gold at Gold Hill?

You’ll find Gold Hill employed both placer and underground methods: gold panning recovered free particles from streams, while miners excavated mine tunnels reaching 800 feet deep. They’d process ore using quicksilver amalgamation and heap-leach cyanide extraction techniques.

How Did Miners Separate Gold From Ore in the 1800S?

You’d crush ore with stamp mills, then use mercury amalgamation—some mines consuming 250-300 pounds annually. Gold panning separated placer deposits, while ore quenching through roasting prepared sulfide-rich rock for chemical extraction, maximizing your yield independence.

What Caused the 1950 Revival Attempt to Fail?

The 1950 revival failed because you couldn’t overcome operational costs exceeding gold’s $35/ounce market value, depleted high-grade ore deposits, and technological limitations. Economic decline made deep-shaft maintenance unprofitable, while growing environmental concerns further constrained extraction methods.

Are There Any Original Mining Structures Still Standing Today?

You’ll find “resting” structures like Barnhardt and Miller Shafts preserved with fencing preservation measures. Site restoration efforts protect the Chilean Ore Mill, Powder House, and steam engines along the 2.2-mile Rail Trail you’re free to explore today.

Can Visitors Pan for Gold at Gold Hill Mines Historic Park?

No verified gold panning rules exist for Gold Hill Mines Historic Park—visitor experiences focus on viewing preserved structures and shafts. You’ll find actual panning opportunities at Reed Gold Mine nearby, where regulations permit hands-on prospecting activities.

References

- https://historicgoldhill.org/experience-the-restored-gold-mining-town-of-gold-hill-nc/

- https://www.dncr.nc.gov/blog/2024/01/16/gold-hill-mining-district-l-81

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold_Hill

- https://historicgoldhill.org

- https://www.ncpedia.org/gold-hill-mine

- http://nationalregister.sc.gov/SurveyReports/HC29003.pdf

- https://www.wfdd.org/culture/2025-08-18/carolina-curious-whats-the-history-of-the-gold-rush-in-north-carolina

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ucgBe1CceT0

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/23518427

- https://www.salisburypost.com/2017/01/22/gold-hills-vivian-hopkins-present-program-history-gold-mining-nc/