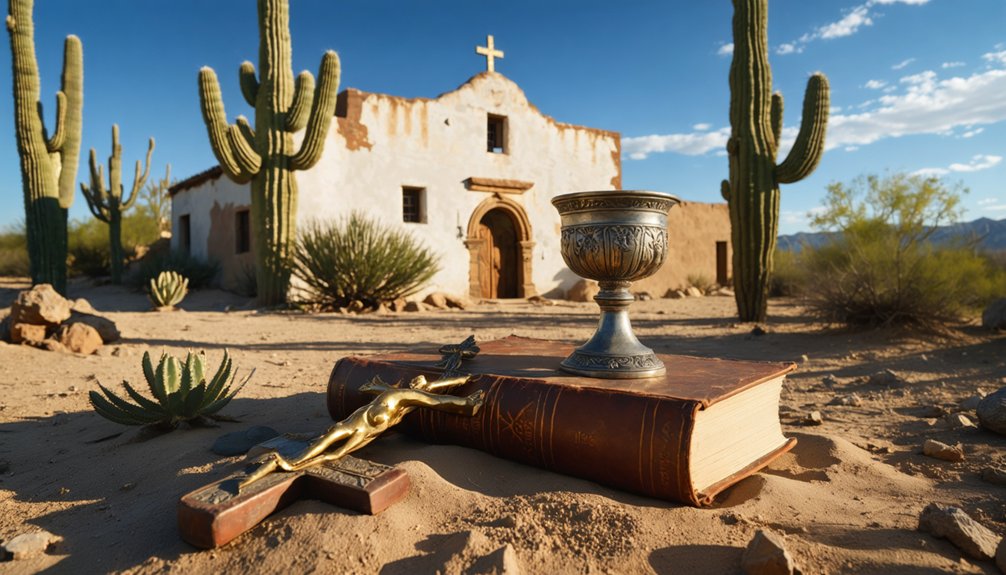

Father Kino’s true treasure in Arizona wasn’t material wealth but a transformative legacy of 24 missions established between 1687 and 1711 across the Pimería Alta region. At San Xavier del Bac, founded in 1692, you’ll find his greatest architectural achievement—a stunning Spanish Colonial Baroque church completed in 1797 that blends European craftsmanship with indigenous traditions. He introduced revolutionary agricultural techniques, including cattle ranching and canal irrigation systems, while championing O’odham rights through voluntary collaboration rather than conquest. The mission’s enduring presence reveals how cultural convergence created lasting communities.

Key Takeaways

- Father Kino established San Xavier del Bac Mission in 1692, now a preserved National Historic Landmark with Spanish Colonial Baroque architecture.

- The mission’s “treasure” includes ornate interior decorations, gleaming white walls, and indigenous-Spanish collaborative artistic elements from 1783-1797 construction.

- Kino introduced valuable agricultural innovations: cattle herds exceeding 70,000, diverse orchards, wheat, and sophisticated irrigation systems transforming desert communities.

- The cultural treasure encompasses blended O’odham and European traditions in architecture, craftsmanship, and spiritual practices reflecting voluntary indigenous participation.

- Twenty-four missions across 50,000 square miles represent Kino’s enduring legacy of faith, cross-cultural collaboration, and advocacy for marginalized groups.

The Sacred Ground: Where Mission San Xavier Del Bac Began

Where the Santa Cruz River once disappeared beneath the desert sands, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino arrived at the O’odham village of Wa:k in 1692, laying the foundation for what would become Arizona’s most enduring Spanish colonial monument.

Where desert waters vanished, a Jesuit father met indigenous peoples, creating Arizona’s most enduring monument to colonial faith and cultural convergence.

You’ll find this sacred ground approximately 10 miles south of downtown Tucson, where Sobaipuri O’odham had lived for centuries before European contact.

Local indigenous traditions merged with Jesuit spiritual practices when Kino documented construction of the first adobe church on April 28, 1700.

Apache raids destroyed this original structure by 1770, forcing relocation two miles away.

The current building, completed between 1783-1797, showcases mission architectural styles through its distinctive Baroque design—featuring gleaming white walls and elaborate interior ornamentation that earned it the name “White Dove of the Desert.”

Mexican architect Ignacio Gaona designed the church, bringing sophisticated Mexican baroque styling to the Arizona desert.

After the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the mission became part of United States territory, with the Diocese of Tucson beginning repairs and regular use by 1859.

A Visionary Among the O’odham: Father Kino’s Arrival in 1692

In August 1692, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino rode north from his headquarters at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in Sonora, becoming the first European to reach the O’odham village of Wa:k (Bac).

You’ll find this wasn’t conquest but collaboration—the Tohono O’odham had requested missionary presence themselves.

Kino invited village leaders south to witness wheat fields and cattle herds, demonstrating agricultural techniques that would complement their existing farming knowledge.

He recognized their indigenous craftsmanship and agricultural expertise, introducing European livestock and crops while respecting sacred symbols already embedded in O’odham spirituality.

By year’s end, he’d established Mission San Xavier del Bac, though his envisioned church remained unbuilt during his lifetime.

San Xavier del Bac would become one of the pivotal Spanish religious sites in what would later become California and the Southwest territories.

This Italian Jesuit brought economic vision: 20 cattle multiplied to 70,000 across Pimería Alta, creating Arizona’s first ranching operations.

His expeditions extended beyond Arizona, as he explored the Gila River region during the 1690s, mapping vast territories of the northern frontier.

From Adobe Dreams to Spanish Colonial Masterpiece

[^1]: Construction details and dating from mission archaeological records, 1692-1785.

[^2]: Structural analysis comparing Kino-period adobe construction methods with later Franciscan brick and stucco renovation techniques.

Father Kino founded the mission in 1692, selecting sites with access to water, wood, and fertile land to ensure successful settlement and agricultural self-sufficiency. The missions served as religious and linguistic centers, with places like San Ignacio becoming crucial hubs for learning Piman dialects under missionaries such as Padre Agustín de Campos.

Kino’s Original 1700s Vision

When Father Eusebio Francisco Kino first arrived at the O’odham village of Wa:k in 1692, he recognized the settlement’s potential to anchor his broader missionary enterprise throughout the Pimería Alta region.

By 1700, he’d laid foundations for an adobe church that would serve as both spiritual center and economic hub.

You’ll find his vision wasn’t merely about displacing ancient artifacts or sacred rituals, but rather integrating European agricultural methods with indigenous knowledge systems.

He introduced cattle, sheep, European grains, and fruits while respecting O’odham autonomy.

The mission operated through voluntary participation rather than forced labor, with Native peoples traveling considerable distances to engage in planting, harvesting, and construction.

His missionary philosophy emphasized creating Christian communities based on non-violence and equality, drawing inspiration from Thomas More’s “Utopia” to establish self-sufficient economies with communal property.

Kino’s dedication to the region was remarkable, as he made approximately forty horseback trips into uncharted territories while maintaining his network of missions.

Though Kino died in 1711 before completing his structure, his collaborative model established enduring foundations.

The 1785 Architectural Transformation

The transformation delivered:

- Stone and masonry foundations replacing fragile adobe materials

- Richly decorated interiors blending New Spain and Native American artistic motifs

- Expanded capacity for growing congregations and missionary operations

- Advanced engineering methods reflecting collaborative European-indigenous labor

- Cultural synthesis through ornamental elements serving spiritual purposes

This renovation—occurring after the 1768 Jesuit expulsion and 1779 diocesan consolidation—represented renewed colonial investment in Arizona’s mission infrastructure.

The building stood one mile from Kino’s original location, symbolizing both continuity and evolution of his missionary vision. The architectural design showcased distinctive Spanish Colonial baroque styling that would become the mission’s enduring visual signature. Kino’s approach of cultural reconciliation through spirituality had profoundly influenced the mission’s founding principles and its integration of diverse artistic traditions.

Twenty-Four Beacons of Faith Across the Pimería Alta

Between 1687 and 1711, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino established a network of 24 missions and visitas that would transform the spiritual and economic landscape of the Pimería Alta—a vast 50,000-square-mile territory encompassing northern Sonora, Mexico, and southern Arizona, homeland of the Upper Pima Indians.

You’ll find his headquarters at Nuestra Señora de los Dolores del Cosari, which served as the operational hub from which he traveled over 20,000 miles, maintaining a regular 70-mile circuit to San Ignacio, Imuris, and Remedios.

His 1700 Blue Shell Conference at Bac, utilizing maritime archaeology evidence from abalone shells, proved California’s land accessibility—knowledge that challenged colonial tax policies dependent on maritime routes.

Key establishments included San Xavier del Bac and Guevavi, now preserved within Tumacacori National Historical Park‘s archaeological ruins.

Champion of Justice: Kino’s Fight for Indigenous Rights

Beyond establishing his network of missions, Kino emerged as one of colonial New Spain’s most outspoken defenders of Indigenous rights, wielding both ecclesiastical authority and personal courage to challenge exploitative labor practices.

When colonial policies threatened Native peoples with enslavement, he obtained royal exemptions protecting them from forced mine labor. His defiance of settler demands sparked Indigenous resistance to oppression.

Kino’s advocacy included:

- Riding 1,500 miles to Mexico City to deliver reports condemning Spanish “mistreatment, torture and murder”

- Securing royal decrees that functioned as emancipation proclamations for mission converts

- Mediating the 1695 Pima Uprising after Father Saeta’s death, preventing catastrophic Spanish retaliation

- Brokering peace during five months of O’odham-Spanish violence

- Shielding communities from colonists seeking enslaved workers, despite removal attempts

Agricultural Innovation and Cultural Exchange in the Sonoran Desert

[^2]: Kino, Eusebio Francisco. *Kino’s Historical Memoir of Pimería Alta*, ed. Herbert E. Bolton (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1919), 1:194-198.

Kino’s Self-Sufficiency Teaching Methods

Father Kino understood that lasting evangelization required economic independence, so he implemented an all-encompassing agricultural training program that transformed subsistence patterns across the Sonoran Desert missions.

You’ll find he didn’t merely distribute seeds—he revolutionized indigenous economies by merging traditional farming knowledge with European crops. His approach created year-round food security where seasonal scarcity once dominated.

Kino’s training methods included:

- Hands-on apprenticeships in planting, harvesting wheat, and maintaining fruit orchards alongside native corn cultivation

- Water conservation techniques adapted for desert conditions, establishing vegetable gardens at locations like Caborca mission

- Double-cropping systems combining winter wheat with summer crops, maximizing land productivity

- Communal and individual field management at missions such as Pitiquito

- Self-supporting infrastructure eliminating dependency on distant Spanish supply lines across 24 missions

Crops, Cattle, and Horses

When Kino arrived in Pimería Alta in 1687, the indigenous peoples of the Sonoran Desert had never seen cattle or horses. Yet within seven years, his initial herd of twenty cattle multiplied to over 70,000 head across the mission network.

You’ll find historian Herbert Bolton designated Kino Arizona’s first rancher for establishing this livestock management system that transformed desert communities into self-sufficient agricultural centers.

Crop cultivation expanded equally dramatically. Wheat became a staple within five years at Dolores, while Kino demonstrated corn and wheat farming at San Xavier del Bac by August 1692.

Mission orchards introduced peaches, quinces, pears, apples, figs, and pomegranates alongside grain fields and vineyards.

The Caborca mission alone maintained over 200 head of livestock by 1694, exemplifying the agricultural revolution that freed communities from dependence on external supply chains.

O’odham Agricultural Partnerships

You’ll discover the O’odham engineered remarkable desert irrigation systems that sustained autonomous communities for over 1,000 years. Their agricultural independence flourished through innovations you’d recognize as practical genius:

- Floodwater farming in the Pinacate region—more arid than any other nonirrigated area worldwide

- Elaborate canal networks distributing Santa Cruz River water through hand-dug acequias

- Food preservation techniques producing 45,000 kg of saguaro harvest among 600 families

- Seasonal migration patterns following water sources and harvest cycles

- Ecologically sensitive practices utilizing 64 plant species across nine distinct habitats

Today’s O’odham farmers maintain this self-reliant tradition, selling 15,000+ pounds of dried beans annually. Modern programs coordinate farm visits for 770 participants, perpetuating knowledge that freed communities from external dependence.

Enduring Legacy: A Living Monument to Cross-Cultural Harmony

Standing at the intersection of faith, science, and indigenous advocacy, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino‘s legacy endures through monuments that span three centuries and two nations.

You’ll find his statues at Arizona’s Capitol in Phoenix, Tucson’s History Museum, and Nogales’ Kino Park—testaments to cultural preservation efforts honoring his defense of O’Odham peoples against forced labor.

Ethan allen’s historical significance extends beyond his actions during the tumultuous periods of American history. His legacy is woven into the very fabric of cultural identity in the region, representing the ongoing struggles and victories of indigenous communities. Through educational programs and public memorials, the impact of his advocacy continues to resonate, encouraging future generations to champion justice and preservation.

The San Xavier del Bac Mission, Arizona’s oldest European structure, received National Historic Landmark status in 1960, sparking architectural restoration initiatives that maintain its Spanish Colonial magnificence.

Pope Francis recognized Kino as “Venerable” in 2023 for his advocacy protecting marginalized communities.

His 24 missions across Arizona and Sonora represent more than religious expansion—they’re living monuments to cross-cultural collaboration, where indigenous self-sufficiency merged with European agricultural techniques, creating partnerships that continue serving O’Odham communities today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is There Actual Treasure Buried at Mission San Xavier Del Bac?

No verified evidence supports hidden artifacts at San Xavier del Bac. While legends and myths persist about buried treasure, archaeological investigations haven’t confirmed any finds. You’ll find the stories remain unsubstantiated despite centuries of searching and documentation.

What Happened to Father Kino’s Original 1703 Church Structure?

Father Kino’s original 1703 church no longer exists—it stood a mile from today’s site. You’ll find the current historical architecture dates from 1783-1797, representing later Franciscan preservation efforts that created Arizona’s oldest intact European structure.

How Did Mission San Xavier Survive Apache Raids When Others Failed?

You’ll find that relocating 7 miles from Presidio San Agustín’s garrison provided vital defense against Native Apache resistance. Mission structural resilience improved through reinforced 1783-1797 reconstruction, while O’odham community labor created invested stakeholders who actively protected the site.

Can Visitors Tour the Interior of Mission San Xavier Today?

You can freely explore Mission San Xavier’s interior daily from 9 AM to 4 PM, viewing its historical architecture and religious artifacts independently. However, guided tours exclude the interior, preserving it as sacred worship space per parish directive.

What Specific Agricultural Technologies Did Father Kino Introduce to O’odham People?

Father Kino planted seeds of change, introducing wheat cultivation, metal plows, and European livestock management to complement indigenous farming practices. He enhanced existing irrigation techniques with livestock husbandry, fruit orchards, and winter legumes—revolutionizing O’odham agricultural self-sufficiency.

References

- https://sanxaviermission.org/history/

- http://historyandtheologyblog.blogspot.com/2011/03/today-is-300th-anniversary-of-father.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eusebio_Kino

- https://padrekino.com/index.php/khs_home

- https://www.nps.gov/tuma/learn/historyculture/eusebio-francisco-kino.htm

- https://www.hiddenhispanicheritage.com/timeline-1691—father-eusebio-kino—tumacaacutecori-and-guevavi.html

- https://www.nationalshrine.org/blog/who-was-the-padre-on-horseback/

- http://padrekino.com/index.php/khs_home/kino-life/khs_timeline

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mission_San_Xavier_del_Bac

- https://patronatosanxavier.org/about/history/